2,200-year-old computer suffers major setback

By Jamie Seidel | news.com.au

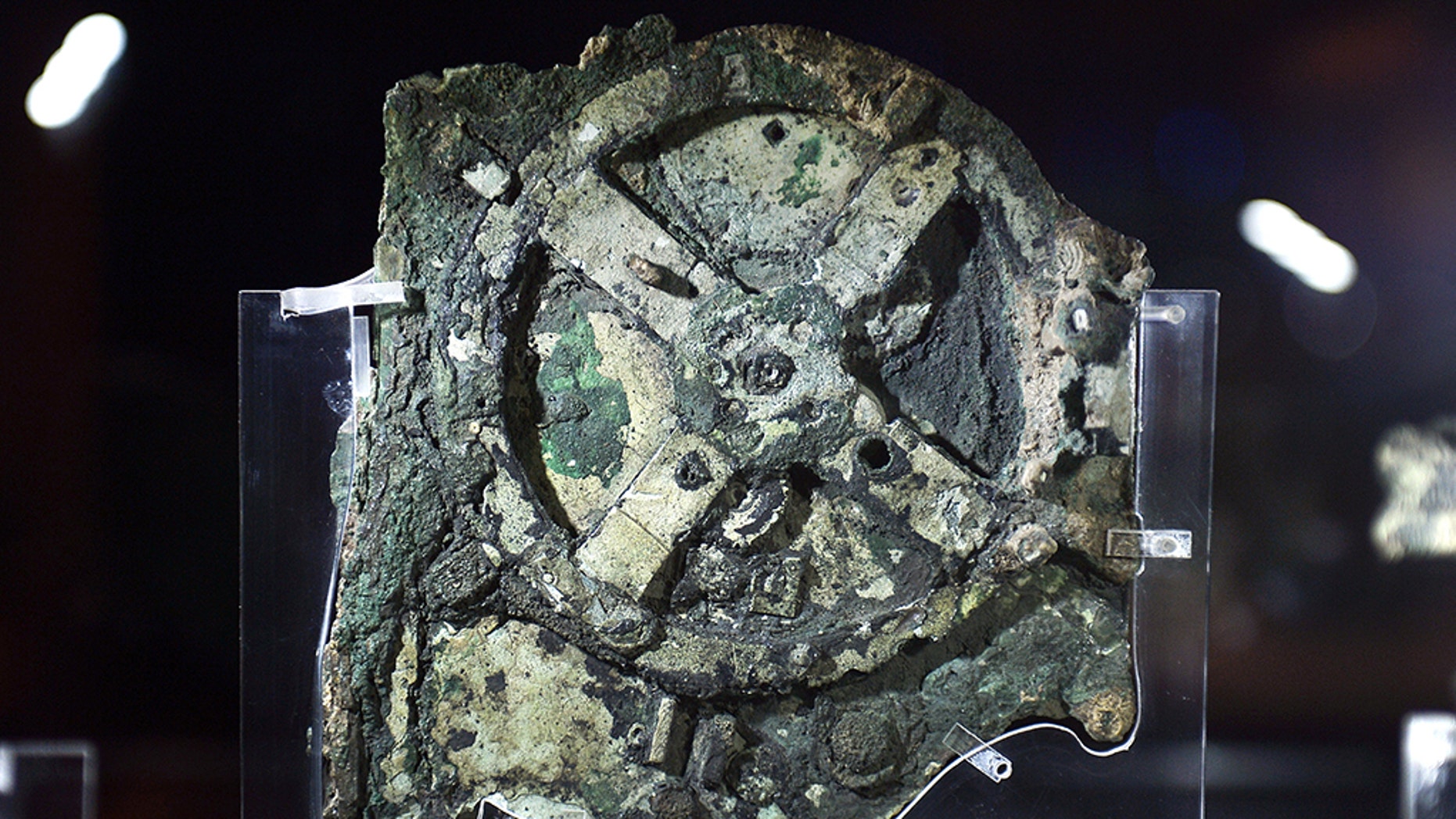

A

picture taken at the Archaeological Museum in Athens on September 14,

2014, shows a piece of the so-called Antikythera Mechanism, a

2nd-century BC device known as the world's oldest computer, which was

discovered by sponge divers in 1900 off a remote Greek island in the

Aegean. The mechanism is a complex mechanical computer which tracked

astronomical phenomena and the cycles of the Solar System.

AFP PHOTO / LOUISA GOULIAMAKI (Credit: LOUISA GOULIAMAKI/AFP/Getty Images)

It fell to the seabed after the ship carrying it was wrecked upon rocks some 2200 years ago. It was one of the ancient world's great wonders. And we had no idea what it was until 50 years after it was rediscovered by divers in 1901. It's a freakishly complex machine. It's a mechanism of bronze cogs and levers used to predict the phases of the sun and moon.

It may have even been far more complex — also capable of calculating the course of the planet and stars through the night sky.

As such, it was a 'divination machine'. A hand-cranked calculator used by priests, prophets and seers to awe audiences with accurate predictions about impending eclipses — and ominous celestial alignments.

So … just how powerful was it?

The analog computer has fascinated a generation of computer entrepreneurs. So a series of expeditions to the small island of Antikythera between Greece and Crete has been funded to see if more fragments of the mysterious device could be recovered.

One tantalizing piece was found on the seabed during an expedition last year. A heavily encrusted bronze disc, about 8cm wide. Now, a new article in the Israeli publication Haaretz has sent a quiver of anticipation around the world.

It declared it to be a lost cog from the Anikythera mechanism itself. And, as it carried the sign of a bull — Taurus — it proves the machine was more complex than many dared dream.

But … not so fast.

MYSTERY OF THE DISC

Since 2012, divers have been returning to Antikythera to scour the steep underwater cliff-face for more treasures.

The wreck was severely damaged by explorer Jean-Jacques Cousteau in the 1970s when he hauled a multitude of marble and bronze statues from the seabed. What remains has been scattered about, or tumbled further into the deep.

The bronze disc, however, seemed promising. It had four protrusions, large 'cog'-like teeth spaced at regular intervals.

It's since been X-rayed and scanned.

It's been found to be engraved with the image of a bull. Is this Taurus, the star constellation and one of the signs of the Zodiac?

Engineers and mathematicians have been struggling to understand the complexity of the Antikythera Mechanism since it was realized to be a metal machine, and not a barnacle encrusted rock, in the 1950s.

Many have attempted to reconstruct the assembly of cogs, wheels and levers.

What is known is it was built by the Greeks and used Babylonian calendar and star observations to calculate the movements of the sun and moon to predict eclipses and equinoxes.

If true, it would be incredible. The combination of such advanced astronomical study, mathematics and mechanical translation would be something not achieved again for another 500 years.

The new disk, if it belonged to the device could confirm its ability to predict the position of the groups of stars so important to the priests and seers of the era.

But … it doesn't.

GREAT EXPECTATIONS

Archaeologists have been quick to point out the new report overemphasizes the importance of the bronze disc.

But, the immense anticipation surrounding anything relating to the mysterious ancient device saw the article circulated quickly and widely … even by experts who should have known better.

What the new disc actually was is unknown.

But the bull-engraved plate is very unlikely to be part of the device's complex workings. If the four protrusions were cogs, they're unusually crude for such a intricate device. Most likely, they were practical attachments for whatever the disc adorned.

At best, the bull-disc could have been an ornamental piece attached to the Antikythera Mechanism's case. But it's just as likely to have decorated some long-decayed panel of wood, or even priestly robes.

Meanwhile, the hunt for more pieces of the mechanism continues.

How many cogs made up the original device is unknown. But inferences based on the positions and fittings attached to the parts already found hint at anywhere between 37 and 70. Others argue there may have actually been two different devices carried on the ship, with their components having become mixed up.

Either way, the manufacturing precision necessary for such a mechanism to work is immense: a slight buckle in just one cog could throw out its calculations or jam its workings.

No comments:

Post a Comment